|

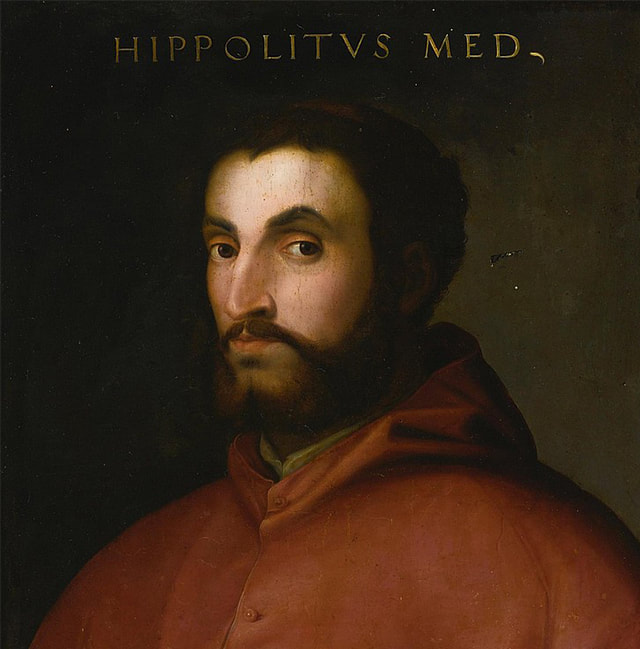

"Portrait of Ms. Blair" by Sir Henry Raeburn, oil on canvas The “Old Masters,” an informal classification in art historical terms, generally refers to European artists dating from approximately the 1500s (the Renaissance) to the 1800s. They were fully trained artists who had become the Masters of their local artists’ guild. In reality, however, many paintings produced by followers of/ school of/ circle of, have also come to fit into today’s catch-all term. Many of the best-known painters of this geographically and historically broad area are considered Old Masters. In advance of a key season of Old Masters auctions, we take a look at this revered category through the lens of portraiture. Our editors spoke with two leading specialists: David Weiss, Senior Vice President and Department Head of European Art & Old Masters at Freeman’s Auctions and Iain Gale, Specialist in Fine Paintings, Sculpture and Scottish Art at Lyon & Turnbull, on why they are optimistic about the market for Old Masters portraits, and how buyers should begin their hunt. Starting a Collection: Old Masters Portraits“Portrait of Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici” by Titian, 16th century, oil on panel Starting a collection of Old Masters portraits can be as broad or as narrow as your means, since this category features artists from a wide range of styles, movements, and geographic locations, including the Renaissance (Gothic, Early, High, Venetian, Sienese, Northern, Spanish), Mannerism, Baroque, the Dutch Golden Age, Flemish and Baroque, Rococo, Neoclacissism, and Romanticism. These schools include some of the most influential painters in Western art history: Titian, Jan Van Eyck, Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Durer, El Greco, Peter Paul Rubens, Artemisia Gentileschi, Diego Velazquez, Frans Hals, Jean-Antoine Watteau, Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, William Hogarth, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Francisco de Goya, William Blake, Eugene Delacroix, and more. Iain Gale advises that anybody wishing to start a collection of Old Masters portraits avoid what he calls a “scattergun” approach. Instead, Gale recommends choosing one centerpiece around which to build a collection, so that works chosen in the future are more likely to reflect the optimal taste of the first. For a new collector with a budget of around £20,000 (~$25,000) to invest, for example, Gale would suggest looking for a work by a Classical painter like Allan Ramsay (1713 – 1784), or the Romantic Henry Raeburn (1756 – 1823). David Weiss suggests that a good place to start is by looking to quality drawings by lesser known, but highly accomplished artists of the 17th and 18th centuries, as these “tend, on balance, to be more affordable than their equivalents rendered in oil.” He also suggests using a limited budget for an early engraving or etching. In offering different approaches to collecting, Gale and Weiss agree on one thing: the market for portraits, Old Masters or otherwise, is a complex one. Ultimately, they note, the motivation of the buyer underscores the value of a work. Collectors may buy portraits for any reason, from “self-aggrandizement to a serious interest in painting,” says Gale. For some, there is concern around buying a portrait of an unknown sitter, somebody else’s ancestry. Overlooked Old Masters While painting from the English Tudor and Stuart periods has always held a high price, much of it, says Gale, still appears stuffy and dark after “years of accumulated dirt and nicotine.” However, he adds, closely inspecting a corner of a work can help to show a painting’s true colors. David Weiss references top tier “school of” or “circle of” paintings, a suggestion he tempers with the caveat that, “this is not to say that landscapes, still lifes, and genre scenes which are direct copies of non-overlooked artist’s paintings deserve a great reception. It is to say that paintings of wonderful quality and skill, and those possessing aesthetic appeal, ought sometimes to sell for more money than they often do vis-à-vis their ‘name brand’ counterparts.” Weiss says that this can be a particularly wise investment because “school of” or “circle of” paintings “of a major artist can, with the passage of time, be determined to be by the artist after whom the work was first thought to be only modeled.” Self-Portraits in a Name-Driven Market “Portrait of a Gentleman Wearing an Embroidered Jacket” by Cornelis Troost, oil on canvas “The moment when a man comes to paint himself – he may do it only two or three times in a lifetime, perhaps never – has in the nature of things a special significance,” wrote Lawrence Gowing in his introduction to a 1962 exhibition of British self-portraits. According to Gale, there is no necessary correlation between value of a painting and whether it is a self-portrait because the value of a work can be determined by many factors. “There is a good market for self-portraits, particularly those that can comfortably be given to the hand of a first or second tier painter, a strong case can be made that there is a correlation between a portrait’s value and the identity of a sitter. It is difficult to argue against a portrait of major historical or noble figure outselling a portrait of a lesser known sitter,” says Weiss, before posing a hypothetical question: “An exceptional self-portrait by a lesser known hand or by a follower or student of a well-known artist versus a self-portrait of only passing quality by an important artist? My money is with the former in the current name-driven art market.” Unless a portrait serves a commemorative purpose, themes and narratives conveyed in a portrait may be subliminal. Such messaging and symbolism tends to include status, wealth, accomplishment, lineage, and power. However, Weiss says, these themes “are not always present in self-portraits, wherein many of the Old Masters sought to and succeeded in presenting themselves in a less grandiose light.” Quality is Key “Portrait of a woman washing clothes,” by Henry Robert Morland, oil on canvas Although the market today is undeniably driven by “name brand” artists, as David Weiss puts it, one crucial factor transcends all others, and both specialists return to the question throughout their responses.

“In my experience, one need only look at some of the offerings in the secondary Old Master auction catalogues of major houses as recently as the 1990s. In many of those sales, the ‘manner of’ and ‘follower of’ paintings that clearly appear to be secondary in quality would either not sell in 2017, or may not even be accepted for consignment in 2017 due to the ever increasing emphasis on quality and on works that are by, or at least have an affiliation with the hand of, an important artist or school,” says Weiss. Determining the value of a painting is a fine balance, the crucial element being an understanding of what motivates the buyer, says Gale. “It may be more visually appealing, and therefore of great value, if a work is by a good hand, even if it is by a minor artist.”

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsWriters, Journalists and Publishers from around the World. Archives

March 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed