|

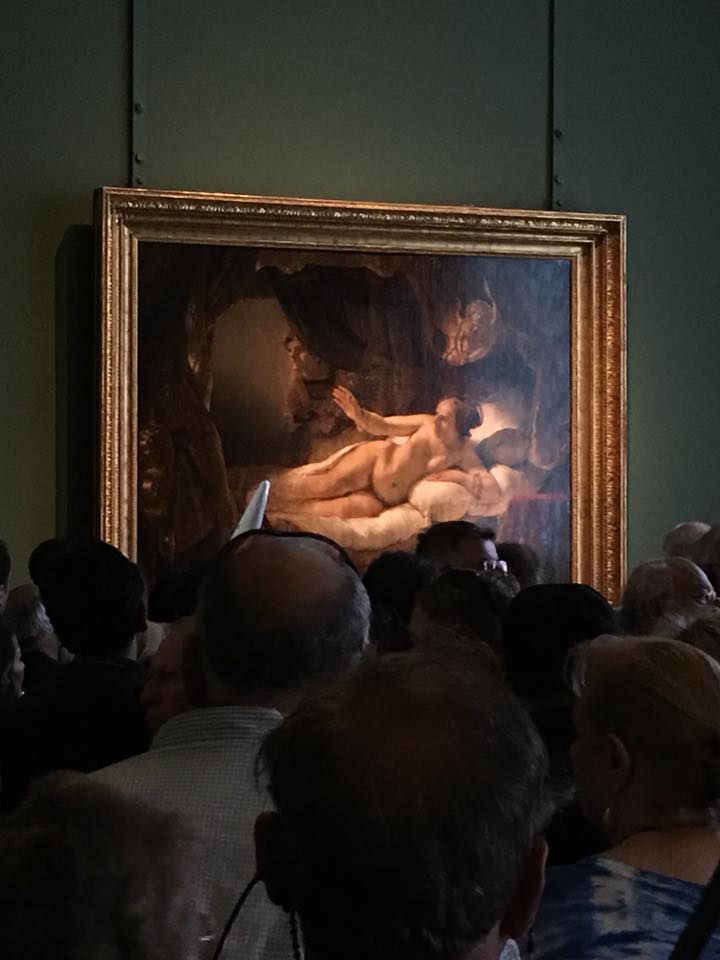

Museum researchers tell us that the average visitor spends just 17 to 27 seconds in front of an artwork - yet such a short window of time won't reveal much about the history of the artwork. So, what should you be looking for when you stand in front of a work of art? Here, Dr Laura-Jane Foley shares her top tips on visual analysis and explains why you - the viewer - are just as important as the person who created it… “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” We’ve all heard the philosophical riddle that makes us question our understanding of perception. If we are not present does something still happen? In the case of a work of art, your presence is paramount, because an artwork needs you more than you might realise. In his seminal work Art and Illusion, first published in 1960, art historian Ernst Gombrich wrote about “the beholder’s share”. It was Gombrich’s belief that a viewer “completed” the artwork, that part of an artwork’s meaning came from the person viewing it. He wasn’t concerned with the artists and what their intentions were; he was interested in what we, the viewers, brought to an artwork. What we project onto an artwork depends on our backgrounds – our upbringing and education, the experiences we’ve had, how we process information, how we look at the world. The meaning we give an image is filtered through all the years of life we’ve lived. Historians, and those with an interest in history, are always keen to explore new periods and broaden their historical knowledge and understanding – but are often put off by images. Despite so many shared features, the ‘history of art’ is always slightly separated from ‘history’. When I was an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge, for example, the history of art department shared a faculty with architecture rather than history.But there are many reasons why historians should welcome history of art into the fold and notbe fearful of images. This fear, or ambivalence, oftenstems from a lack of understanding about what to do in front of a work of art – and it is perfectly understandable. Visual literacy is not encouraged at school and most people interested in general history would be flummoxed by the idea of undertaking a visual analysis of an artwork. And yet, a formal analysis – spending time in front of an artwork, looking closely at the image – is one of the basic elements of art history. The good news for those who want to understand artworks a little better is that it is both deeply rewarding and easy to do. What should I look for?A visual analysis begins by looking, really looking, at an image. Museum researchers tell us that the average visitor spends just 17 to 27 seconds in front of an artwork. No wonder people are so convinced art is hard to understand if they’re spending so little time engaging with it. I don’t think I’d get very far understanding the Franco-Prussian War if I just listened to half a minute of a lecture. We need to slow down and start noticing all the elements of an artwork. Before rushing ahead to consider content and context, simply consider the basic formal elements of the image: line, colour, shape and form. Here’s a brief guide to get you started… Lines Let’s imagine we’re looking at a painting on a canvas. Firstly, focus on the lines– look at what sort of marks have been made on the picture surface and try and describe them. Is the line thick, bold, expressive or dotted, etc? What emotions or moods do these lines and marks suggest to you? Are the lines horizontal or vertical and what is the effect of these lines? Are some lines more noticeable than others? Do they dominate the image? For what purpose? Are the shapes in the painting outlined? What is the effect? Can you see under-drawing or any other marks underneath the painting? Has there been an attempt to disguise these? Colour Next look at colour. What colour scheme has been used? Unmixed primary colours? Secondary colours? Are the colours complementary? Monochrome? Cool or warm? Is the palette broad or muted? Do any colours dominate the canvas? Does the choice of colour make you feel anything in particular? What is the effect of the colour choices? Are the colours bold and vibrant, or pale and muted? All the time when looking at the formal qualities, ask yourself what the effect is of their appearance in the artwork. For example, if the image is in black and white monochrome, what does it remind you of? Newspapers or old photographs, perhaps? Does the absence of colour give the artwork a sense of a loss? Or does the monochrome palette shift the focus of the painting onto another element – like its form or content? ‘The Triumph of Death’ by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1562–3. (Photo by Remo Bardazzi / Electa / Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images) Shapes and forms Next in your visual analysis, look at the shapes and forms. Is the scheme geometric, angular or free-flowing? Are the shapes irregular, simple or complex? Are the shapes/forms repeated and what is the effect of this? How are the shapes arranged? Are they grouped together, or far apart? Are they overlapping? Do they fuse with other shapes/forms? What are the edges of the shapes and form like? Are they distinct or fuzzy? Are there any relief (3D) elements to the painting? Does the paint build up sculpturally on the canvas? Is any other material added to the canvas? What about perspective? Is there a vanishing point? Is there an illusion of the three-dimensional on the two-dimensional picture surface? This is a very brief guide to what a formal visual analysis of a painting is – there’s plenty more to look at and discuss – but I hope it gives you a way in. The main tip is to observe and describe the formal elements of the artwork generally and in detail, before analysing it in relation to any external factors. Because when we deeply observe an artwork, we see and understand so much more and this ultimately leads to achieving a greater enjoyment from looking at art. Content Having completed a formal analysis then it is time to move on to content. Simply, what are you looking at. What, or who, is being depicted, if anything. Are any scenes or figures recognisable from history, religious stories, current affairs, or pop culture? Or do they perhaps remind you of something in your own life? Can you work out the relationship of the figures to each other in the artwork? What can we tell about them from the clothes they wear, the poses they adopt or the expression on their faces? What objects, props or places are included in the artwork? Are they recognisable? Are they symbolic? Finally, what is the title of the artwork? Does it enhance your understanding? Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette’ by Pierre Auguste Renoir, 1876. (Photo by: Christophel Fine Art/UIG via Getty Images) Context

Finally, we look at context and this is where history of art and history are as one. This is the critical analysis; the point at which we explore and evaluate all the social, political, economic and cultural factors that may have had a bearing on the artwork or the artist, or were simply present at the time when the artwork was created. We also can look at what comparisons can be made with other artworks or artists. And this is the point to ask what was the artist’s original intention in creating the artwork and where was it originally displayed? So we only look at the artist at the very end. The most important person in the whole process is you. What do youthink when you look at an artwork? You are at the centre of the visual analysis. Gombrich was quite right: it is the viewer who completes the artwork. So my advice for getting more out of art is to spend more time in front of it and to look really closely, because you are the only critic who matters.

0 Comments

The Blue Boy (ca. 1770) by Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) shown in normal light photography (left), digital x-radiography (center, including a dog previously revealed in a 1994 x-ray), and infrared reflectography ight). Oil on canvas, 70 5/8 x 48 3/4. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. The exhibition “Project Blue Boy” will open at The Huntington LibraryArt Collections, and Botanical Gardens on Sept. 22, 2018, offering visitors a glimpse into the technical processes of a senior conservator working on the famous painting as well as background on its history, mysteries, and artistic virtues. One of the most iconic paintings in British and American history, The Blue Boy, made around 1770 by English painter Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), is undergoing its first major conservation treatment. Home to the work since its acquisition by founder Henry E. Huntington in 1921, The Huntington will conduct some of the project in public view, as part of a year-long educational exhibition that runs through Sept. 30, 2019.

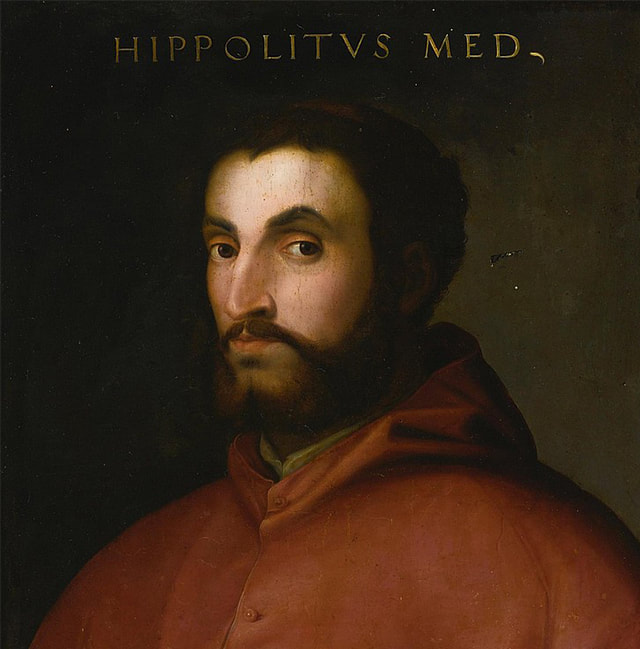

The Blue Boy requires conservation to address both structural and visual concerns. “Earlier conservation treatments mainly have involved adding new layers of varnish as temporary solutions to keep it on view as much as possible,” said Christina O’Connell, The Huntington’s senior paintings conservator working on the painting and co-curator of the exhibition. “The original colors now appear hazy and dull, and many of the details are obscured.” According to O’Connell, there are also several areas where the paint is beginning to lift and flake, making the work vulnerable to paint loss and permanent damage; and the adhesion between the painting and its lining is separating, meaning it does not have adequate support for long-term display. During three months of preliminary analysis—which was carried out by conservators in 2017, with results reviewed by curators—the painting was examined and documented using a range of imaging techniques that allow O’Connell and Melinda McCurdy, The Huntington’s associate curator for British art and co-curator of the exhibition, to see beyond the surface with wavelengths the human eye can’t see. Infrared reflectography rendered some paints transparent, making it possible to see preparatory lines or changes the artist made. Ultraviolet illumination made it possible to examine and document the previous layers of varnish and old overpaints. New images of the back of the painting were taken to document what appears to be an original stretcher (the wooden support to which the canvas is fastened) as well as old labels and inscriptions that tell more of the painting’s story. And, minute samples from the 2017 technical study and from previous analysis by experts were studied at high magnification (200-400x) with techniques including scanning electron microscopy with which conservators could scrutinize specific layers and pigments within the paint. Armed with information gathered from the 2017 analysis, the co-curators mapped out a course of action for treating the painting and developed a series of questions for which they are eager to find answers. “One area we’d like to better understand is, what technical means did Gainsborough use to achieve his spectacular visual effects?” said McCurdy. “He was known for his lively brushwork and brilliant, multifaceted color. Did he develop special pigments, create new materials, pioneer new techniques? We know from earlier x-rays that The Blue Boy was painted on a used canvas, on which the artist had begun the portrait of a man,” she said. “What might new technologies tell us about this earlier abandoned portrait? Where does this lost painting fit into his career? How does it compare with other earlier portraits by Gainsborough?” As the conservation process continues, McCurdy also looks forward to discovering other evidence that may become visible beneath the surface paint, and what it might indicate about Gainsborough’s painting practice. In fact, the undertaking, supported by a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project, already has uncovered new information of interest to art historians. During preliminary analysis, conservators found an L-shaped tear more than 11 inches in length, which data suggest was made early in the painting’s history. The damage may have occurred during the 19th century when the painting was in the collection of the Duke of Westminster and exhibited frequently. Further technical evidence combined with archival research may help pinpoint a more precise date for this tear, and even reveal its probable cause. “Project Blue Boy” Visitor Experience For the first three to four months during the year-long exhibition, The Blue Boy will be on public view in a special satellite conservation studio set up in the west end of the Thornton Portrait Gallery, where O’Connell will work on the painting to continue examination and analysis, as well as begin paint stabilization, surface cleaning, and removal of non-original varnish and overpaint. It then will go off view for another three to four months while she performs structural work on the canvas and applies varnish with equipment that can’t be moved to the gallery space. Once structural work is complete, The Blue Boy will return to the gallery where visitors can witness the inpainting process until the close of the exhibition. During the two periods when the painting is in the gallery, O’Connell will work in public view on regularly scheduled days and times. For the first in-gallery period, from Sept. 22 through January 2019 (estimated), visitors can watch the process each Thursday and Friday from 10 a.m. to noon and from 2 to 4 p.m., and on the first Sunday of each month from 2 to 4 p.m. A similar schedule will be in place during the second in-gallery session, estimated to begin in summer 2019. Schedule updates will be posted on the web at huntington.org/projectblueboy. When O’Connell is working in the gallery she might use any number of tools, the largest among them a Haag-Streit Hi-R NEO 900 surgical microscope that measures six feet in height. The state-of-the-art device has a long movable arm and optics that can magnify up to 25x to give the conservator a detailed view of the painting’s surface during the treatment stages, when special adhesives will be added to the areas of lifting paint. Many of the conservator’s hand tools will be showcased, giving visitors a chance to understand the precision inherent in the work. “When the painting is not in the gallery, visitors will still have plenty to see,” said O’Connell. A display with multiple educational modules will tease out details relating to the project and illuminate the painting’s structure and materials, condition and treatment plans, and an explanation of the conservation profession. An interactive light box will show the latest digital x-rays of the work; one iPad will allow visitors to explore more deeply the conservation science involved, and another will provide historical background on the painting and artist. Actual conservation tools will be on display, and behind a low wall, the temporary conservation studio will be in plain view, equipped with all the necessary trappings—work tables, easel, conservation lights, and exhaust units, as well as a whiteboard where O’Connell will post updates on what is currently happening and the times when she’ll be available to answer visitor questions. Also, specially trained docents will be stationed in the gallery throughout the run of the exhibition to illuminate the project and answer questions. After the close of the exhibition, the painting will go back to the lab for final treatment and reframing. Finally, in early 2020, The Blue Boy will be rehung in its former spot at the west end of the portrait gallery and unveiled as a properly stabilized masterpiece with more of the vivid pigments and technical brilliance it radiated when it debuted at the Royal Academy some 250 years ago again visible to viewers. The curators of “Project Blue Boy” plan to share their findings in lectures and publications after the completion of the project. The Huntington's website will track the project as it unfolds at huntington.org/projectblueboy. Related Programs “Project Blue Boy” will be accompanied by an array of public programs, including scholarly lectures, curator tours, and family activities. About The Blue Boy Thomas Gainsborough was among the most prominent artists of his day. Though he preferred to paint landscapes, he made his career producing stylish portraits of the British gentry and aristocracy. Jonathan Buttall (1752–1805), the first owner of The Blue Boy, was once thought to have been the model for the painting, but the identity of the subject remains unconfirmed. The subject’s costume is significant. Instead of dressing the figure in the elegant finery worn by most sitters at the time, Gainsborough chose knee breeches and a slashed doublet with a lace collar–-a clear nod to the work of Anthony van Dyck, the 17th-century Flemish painter who had profoundly influenced British art. The painting first appeared in public in the Royal Academy exhibition of 1770 as A Portrait of a Young Gentleman, where it received high acclaim, and by 1798 it was being called “The Blue Boy”–-a nickname that stuck. Henry E. Huntington (1850–1927) purchased The Blue Boy in 1921 for $728,000, the highest price ever paid for a painting at the time. By bringing a British treasure to the United States, Huntington imbued an already well-known image with even greater notoriety on both sides of the Atlantic. Before allowing the painting to be transferred to San Marino, art dealer Joseph Duveen orchestrated an international publicity campaign that rivaled those surrounding blockbuster movies today. In its journey from London to Los Angeles, The Blue Boy underwent a shift from portrait to icon, as the focus of a series of limited-engagement exhibitions engineered by Duveen. The image remains recognizable to this day, appearing in works of contemporary art and in vehicles of popular culture—from major motion pictures to velvet paintings. But beyond its cultural significance, the painting is considered a masterpiece of artistic virtuosity. Gainsborough’s command of color and mastery of brushwork are on full display in the painting, and they are expected to become more apparent as a result of “Project Blue Boy” conservation work. "Portrait of Ms. Blair" by Sir Henry Raeburn, oil on canvas The “Old Masters,” an informal classification in art historical terms, generally refers to European artists dating from approximately the 1500s (the Renaissance) to the 1800s. They were fully trained artists who had become the Masters of their local artists’ guild. In reality, however, many paintings produced by followers of/ school of/ circle of, have also come to fit into today’s catch-all term. Many of the best-known painters of this geographically and historically broad area are considered Old Masters. In advance of a key season of Old Masters auctions, we take a look at this revered category through the lens of portraiture. Our editors spoke with two leading specialists: David Weiss, Senior Vice President and Department Head of European Art & Old Masters at Freeman’s Auctions and Iain Gale, Specialist in Fine Paintings, Sculpture and Scottish Art at Lyon & Turnbull, on why they are optimistic about the market for Old Masters portraits, and how buyers should begin their hunt. Starting a Collection: Old Masters Portraits“Portrait of Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici” by Titian, 16th century, oil on panel Starting a collection of Old Masters portraits can be as broad or as narrow as your means, since this category features artists from a wide range of styles, movements, and geographic locations, including the Renaissance (Gothic, Early, High, Venetian, Sienese, Northern, Spanish), Mannerism, Baroque, the Dutch Golden Age, Flemish and Baroque, Rococo, Neoclacissism, and Romanticism. These schools include some of the most influential painters in Western art history: Titian, Jan Van Eyck, Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Durer, El Greco, Peter Paul Rubens, Artemisia Gentileschi, Diego Velazquez, Frans Hals, Jean-Antoine Watteau, Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, William Hogarth, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Francisco de Goya, William Blake, Eugene Delacroix, and more. Iain Gale advises that anybody wishing to start a collection of Old Masters portraits avoid what he calls a “scattergun” approach. Instead, Gale recommends choosing one centerpiece around which to build a collection, so that works chosen in the future are more likely to reflect the optimal taste of the first. For a new collector with a budget of around £20,000 (~$25,000) to invest, for example, Gale would suggest looking for a work by a Classical painter like Allan Ramsay (1713 – 1784), or the Romantic Henry Raeburn (1756 – 1823). David Weiss suggests that a good place to start is by looking to quality drawings by lesser known, but highly accomplished artists of the 17th and 18th centuries, as these “tend, on balance, to be more affordable than their equivalents rendered in oil.” He also suggests using a limited budget for an early engraving or etching. In offering different approaches to collecting, Gale and Weiss agree on one thing: the market for portraits, Old Masters or otherwise, is a complex one. Ultimately, they note, the motivation of the buyer underscores the value of a work. Collectors may buy portraits for any reason, from “self-aggrandizement to a serious interest in painting,” says Gale. For some, there is concern around buying a portrait of an unknown sitter, somebody else’s ancestry. Overlooked Old Masters While painting from the English Tudor and Stuart periods has always held a high price, much of it, says Gale, still appears stuffy and dark after “years of accumulated dirt and nicotine.” However, he adds, closely inspecting a corner of a work can help to show a painting’s true colors. David Weiss references top tier “school of” or “circle of” paintings, a suggestion he tempers with the caveat that, “this is not to say that landscapes, still lifes, and genre scenes which are direct copies of non-overlooked artist’s paintings deserve a great reception. It is to say that paintings of wonderful quality and skill, and those possessing aesthetic appeal, ought sometimes to sell for more money than they often do vis-à-vis their ‘name brand’ counterparts.” Weiss says that this can be a particularly wise investment because “school of” or “circle of” paintings “of a major artist can, with the passage of time, be determined to be by the artist after whom the work was first thought to be only modeled.” Self-Portraits in a Name-Driven Market “Portrait of a Gentleman Wearing an Embroidered Jacket” by Cornelis Troost, oil on canvas “The moment when a man comes to paint himself – he may do it only two or three times in a lifetime, perhaps never – has in the nature of things a special significance,” wrote Lawrence Gowing in his introduction to a 1962 exhibition of British self-portraits. According to Gale, there is no necessary correlation between value of a painting and whether it is a self-portrait because the value of a work can be determined by many factors. “There is a good market for self-portraits, particularly those that can comfortably be given to the hand of a first or second tier painter, a strong case can be made that there is a correlation between a portrait’s value and the identity of a sitter. It is difficult to argue against a portrait of major historical or noble figure outselling a portrait of a lesser known sitter,” says Weiss, before posing a hypothetical question: “An exceptional self-portrait by a lesser known hand or by a follower or student of a well-known artist versus a self-portrait of only passing quality by an important artist? My money is with the former in the current name-driven art market.” Unless a portrait serves a commemorative purpose, themes and narratives conveyed in a portrait may be subliminal. Such messaging and symbolism tends to include status, wealth, accomplishment, lineage, and power. However, Weiss says, these themes “are not always present in self-portraits, wherein many of the Old Masters sought to and succeeded in presenting themselves in a less grandiose light.” Quality is Key “Portrait of a woman washing clothes,” by Henry Robert Morland, oil on canvas Although the market today is undeniably driven by “name brand” artists, as David Weiss puts it, one crucial factor transcends all others, and both specialists return to the question throughout their responses.

“In my experience, one need only look at some of the offerings in the secondary Old Master auction catalogues of major houses as recently as the 1990s. In many of those sales, the ‘manner of’ and ‘follower of’ paintings that clearly appear to be secondary in quality would either not sell in 2017, or may not even be accepted for consignment in 2017 due to the ever increasing emphasis on quality and on works that are by, or at least have an affiliation with the hand of, an important artist or school,” says Weiss. Determining the value of a painting is a fine balance, the crucial element being an understanding of what motivates the buyer, says Gale. “It may be more visually appealing, and therefore of great value, if a work is by a good hand, even if it is by a minor artist.” Detail of Vigée Le Brun’s Self Portrait in a Straw Hat (after 1782). The French portraitist was the subject of a major survey in Paris, New York and Ottawa (Photo: © National Gallery, London)

|

AuthorsWriters, Journalists and Publishers from around the World. Archives

March 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed