|

In the late 19th century, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933), son of Tiffany & Co. founder Charles Lewis Tiffany (1812–1902), strayed from the family business to become one of the most pivotal artists and designers of the Art Nouveau movement. Tiffany Studios: A Brief HistoryBorn in New York to a family of prominent, high-end jewelry-makers, Tiffany was afforded the opportunity to travel at a young age. His first moment of inspiration emerged from a visit to London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 1865, where he encountered luminous colors achieved by glassware from antiquity. Just 20 years later, he opened Tiffany Studios, a glassmaking studio that quickly rose to prominence through a series of high-profile commissions that included designs for New York’s Lyceum Theater and the White House in Washington, D.C. As a result of his early exposure to decorative art from around the world, his designs drew inspiration from global sources such as Persian glass design, stained glass windows of the Gothic movement, and other elements of Asian and European craftsmanship. Tiffany lamps contained coiled bronze wire and blown favrile glass (a term that Tiffany himself coined) that “reflected the cultural fascination with the exotic,” says Tim Andreadis, Freeman’s specialist in 20th century design. From the late 1890s through the 1920s, Tiffany Studios produced mosaic glass shades that featured geometric and floral motifs. His geometric patterns invoked the far-reaching Arts and Crafts movement that defined the turn of the 20th century, while his nature-inspired motifs aligned with the Art Nouveau movement, a style that punctuated turn-of-the-century art, architecture, advertising, and design. The artists and designers who developed the iconic Tiffany lamp shade, says Andreadis, “established an oeuvre of lighting design unmatched in the modern era.” Antique Tiffany Lamps ValueAntique Tiffany lamps are sought-after today and the market remains competitive for investment-quality works. Tiffany lamps’ value can be anywhere from $4,000 to over $1 million. The most expensive Tiffany lamps sell for upwards of $1 million. The highest price ever paid for a Tiffany lamp remains $2.8 million at a Christie’s auction in 1997. “The very best Tiffany lamps have harmoniously composed shades from a mosaic of hundreds of individually selected glass pieces,” says Andreadis. “A very good example can be acquired on today’s market in the $100,000-150,000 price range.” Tiffany lamps bearing floral motifs and vibrant colors are among the most in-demand examples in the market today. Some of the most popular designs range from the more orientalist styles like the Tiffany Poppy lamp, to the dream-like, flowing floral designs like the Tiffany Daffodil lamp and the Tiffany Wisteria lamp. The Tiffany Dragonfly and Tiffany Peacock lamps, says Andreadis, are among the most desirable of the “blue-chip” Tiffany lamps – those that would have been much more expensive at the time of their creation and still tend to fetch six-figure values today. Popular Motifs for Tiffany LampsSome of the popular Tiffany lamp motifs in the market include:

Tiffany Floor Lamps Image 1: Tiffany Studios Hanging Head “Dragonfly” Floor Lamp Sotheby’s, New York, NY (December 2017) Estimate: $300,000 – $500,000 Price Realized: $550,000 Image 2: Tiffany Studios Patinated-Bronze and Leaded Favrile Glass Poinsettia Floor Lamp Doyle New York, New York, NY (September 2004) Estimate: $150,000 – $200,000 Price Realized: $317,500 Image 3: Tiffany Studios Intaglio-Carved Favrile Glass, Turtleback Tile and Bronze Counter Balance Floor Lamp Christie’s, New York, NY (December 2000) Estimate: $18,000 – $24,000 Price Realized: $25,850 Image 4: Tiffany Studios Butterfly Etched Iridescent Favrile Glass and Bronze Counterbalance Floor Lamp Waddington’s, Toronto, ON (June 2009) Estimate: CAD8,000 – CAD12,000 Price Realized: CAD25,200 Image 5: Tiffany Studios, Leaded Daffodil Floor Lamp James D. Julia, Fairfield, ME (November 2012) Estimate: $1,000 – $1,500 Price Realized: $13,800 Image 6: Tiffany Studios A Favrile Glass and Patinated Bronze Floor Lamp, circa 1900 Bonhams, London, United Kingdom (October 2015) Estimate: Unavailable Price Realized: £1,500 Tiffany Table Lamps Image 7: Tiffany Studios Wisteria Table Lamp Phillips, New York, NY (December 2012) Est: $500,000 – $700,000 Sold: $506,500 Image 8: Tiffany Studios, Important Peacock Table Lamp Sotheby’s, New York, NY (December 2015) Estimate: $300,000 – $500,000 Price Realized: $370,000 Image 9: Tiffany Studios Dragonfly Table Lamp James D. Julia, Fairfield, ME (June 2017) Estimate: $25,000 – $35,000 Price Realized: $51,425 Image 10: Tiffany Studios, Tall Table Lamp with Greek Key Rago Arts and Auction Center, Lambertsville, NJ (October 2013) Estimate: $14,000 – $19,000 Price Realized: $15,000 Tiffany Hanging Lamps Image 11: Tiffany Studios Poppy Chandelier Sotheby’s, New York, NY (December 2017) Estimate: $200,000 – $300,000 Price Realized: $500,000 Image 12: Tiffany Studios Dragonfly Chandelier James D. Julia, Fairfield, ME (June 2017) Estimate: $100,000 – $150,000 Price Realized: $228,100 Image 13: Tiffany Studios Daffodil Hanging Chandelier Cottone Auctions, Geneseo, NY (March 2017) Estimate: $35,000 – $55,000 Price Realized: $51,750 Image 14: Unsigned Tiffany Studios Bronze and Leaded Favrile Glass Turtle Back and Geometric Hanging Shade Doyle New York, New York, NY (September 2012) Estimate: $8,000 – $12,000 Price Realized: $18,750 Image 15: Tiffany Studios Three-Arm Chandelier James D. Julia, Fairfield, ME (November 2014) Estimate: $10,000 – $15,000 Price Realized: $10,497 Image 16: A Tiffany Studios Favrile glass turtle back tile ceiling fixture Bonhams, New York, NY (December 2014) Estimate: $8,000 – $12,000 Price Realized: $8,750 Tiffany Desk Lamps In case six-figure sums aren’t in your budget, Tiffany Studios also produced student and library lamps with geometric or favrile glass shades. Seeking these out, as well as some of the less popular motifs and original components of Tiffany lamps allow for buyers to “acquire Tiffany quality at a fraction of the price of the more elaborate leaded lamps,” says Andreadis. Another more accessible option for those seeking Tiffany Studios lamps is the bronze base. While less breathtaking than their lampshade counterparts, original bases are still valued by collectors. Image 17: Tiffany Studios Bronze and Favrile Glass Desk Lamp Doyle New York, New York, NY (June 2003) Estimate: $10,000 – $15,000 Price Realized: $14,000 Image 18: Tiffany Studios Bronze and Favrile Glass Three-Light Desk Lamp Heritage Auctions, Dallas, TX (November 2014) Estimate: $2,000 – $4,000 Price Realized: $8,125 Image 19: Tiffany Studios Nautilus Desk Lamp James D. Julia, Fairfield, ME (June 2016) Estimate: $8,000 – $12,000 Price Realized: $7,702 Image 20: Tiffany Studios Bronze Counter-Balance Desk Lamp Rago Arts and Auction Center, Lambertsville, NJ (March 2008) Estimate: $4,500 – $6,500 Price Realized: $4,000 Image 21: Tiffany Studios Bronze Three-Light “Lily” Desk or Piano Lamp New Orleans Auction Galleries, New Orleans, LA (December 2017) Estimate: $800 – $1,200 Price Realized: $3,200 How to Identify Antique Tiffany LampsHow can you tell that your leaded lamp is an original Tiffany lamp? Here are a few tell-tale hallmarks of an original Tiffany lamp:

When in doubt, always contact a decorative art specialist specialist, who can offer better insight on your particular example.

0 Comments

A famous work by Russian realist painter Ilya Repin was vandalized by a visitor at Moscow's Tretyakov Gallery on May 25. Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on November 16th, 1581, a painting dating from 1885, was seriously damaged in the attack, in which the man used a metal fence post to smash the protection glass and rip the canvass.

"The painting is badly damaged, the canvas is ripped in three places in the central part ... The falling glass also damaged the frame," the Gallery said in a statement. "Luckily, the most valuable images, those of the faces and hands of the tsar and prince were not damaged," the statement said. The attacker was detained and a criminal case was brought against him, the Interior Ministry reported, without revealing his identity. Russian news agency TASS quoted an unnamed law enforcement official as saying the perpetrator was a 37-year-old man from Voronezh, a city some 525 kilometers south of Moscow, who attacked the painting because of the "falsehood of the historical facts depicted on the canvas." READ MORE: Russia's Dangerous Struggle With Obscurantism The painting depicts Ivan the Terrible mortally wounding his son in Ivan in a fit of rage, and it is considered the most psychologically intense of Repin’s paintings -- an expression of the artist's revolt against violence and bloodshed. The painting was subjected to vandalism for the first time in 1913, when Abram Balashov, a mentally ill man, cut it with a knife in three places. Repin himself participated then in the restoration of the painting, the gallery said in its statement. The Blue Boy (ca. 1770) by Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) shown in normal light photography (left), digital x-radiography (center, including a dog previously revealed in a 1994 x-ray), and infrared reflectography ight). Oil on canvas, 70 5/8 x 48 3/4. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. The exhibition “Project Blue Boy” will open at The Huntington LibraryArt Collections, and Botanical Gardens on Sept. 22, 2018, offering visitors a glimpse into the technical processes of a senior conservator working on the famous painting as well as background on its history, mysteries, and artistic virtues. One of the most iconic paintings in British and American history, The Blue Boy, made around 1770 by English painter Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), is undergoing its first major conservation treatment. Home to the work since its acquisition by founder Henry E. Huntington in 1921, The Huntington will conduct some of the project in public view, as part of a year-long educational exhibition that runs through Sept. 30, 2019.

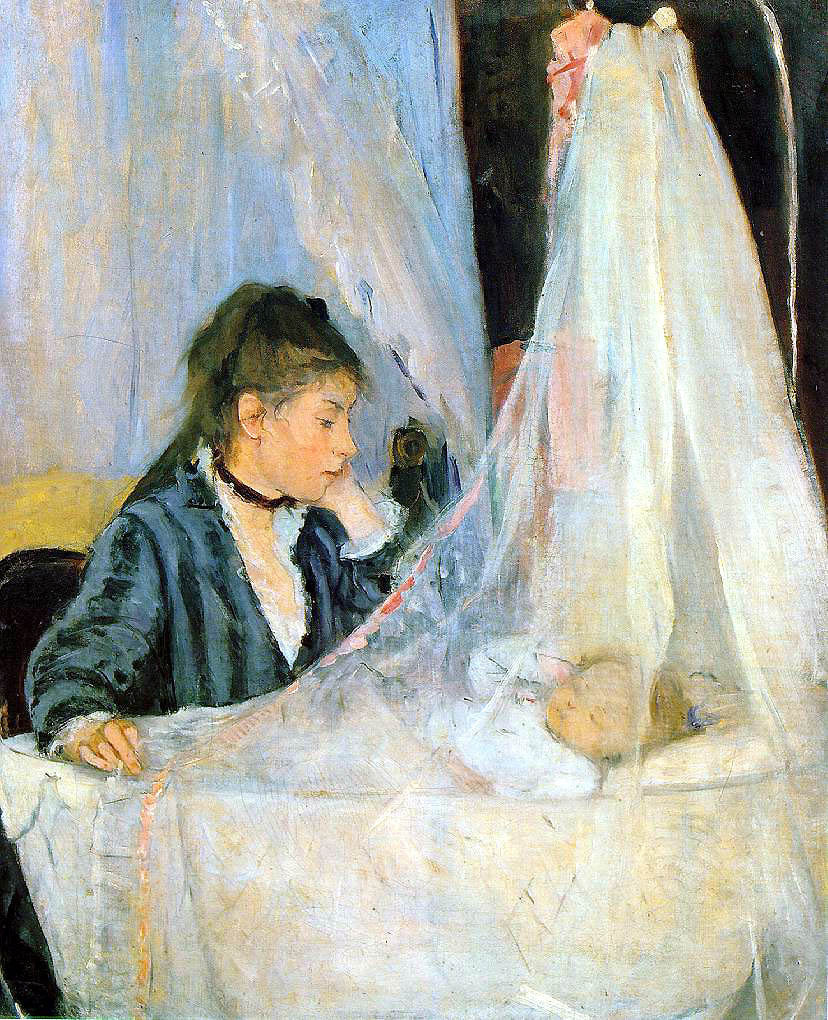

The Blue Boy requires conservation to address both structural and visual concerns. “Earlier conservation treatments mainly have involved adding new layers of varnish as temporary solutions to keep it on view as much as possible,” said Christina O’Connell, The Huntington’s senior paintings conservator working on the painting and co-curator of the exhibition. “The original colors now appear hazy and dull, and many of the details are obscured.” According to O’Connell, there are also several areas where the paint is beginning to lift and flake, making the work vulnerable to paint loss and permanent damage; and the adhesion between the painting and its lining is separating, meaning it does not have adequate support for long-term display. During three months of preliminary analysis—which was carried out by conservators in 2017, with results reviewed by curators—the painting was examined and documented using a range of imaging techniques that allow O’Connell and Melinda McCurdy, The Huntington’s associate curator for British art and co-curator of the exhibition, to see beyond the surface with wavelengths the human eye can’t see. Infrared reflectography rendered some paints transparent, making it possible to see preparatory lines or changes the artist made. Ultraviolet illumination made it possible to examine and document the previous layers of varnish and old overpaints. New images of the back of the painting were taken to document what appears to be an original stretcher (the wooden support to which the canvas is fastened) as well as old labels and inscriptions that tell more of the painting’s story. And, minute samples from the 2017 technical study and from previous analysis by experts were studied at high magnification (200-400x) with techniques including scanning electron microscopy with which conservators could scrutinize specific layers and pigments within the paint. Armed with information gathered from the 2017 analysis, the co-curators mapped out a course of action for treating the painting and developed a series of questions for which they are eager to find answers. “One area we’d like to better understand is, what technical means did Gainsborough use to achieve his spectacular visual effects?” said McCurdy. “He was known for his lively brushwork and brilliant, multifaceted color. Did he develop special pigments, create new materials, pioneer new techniques? We know from earlier x-rays that The Blue Boy was painted on a used canvas, on which the artist had begun the portrait of a man,” she said. “What might new technologies tell us about this earlier abandoned portrait? Where does this lost painting fit into his career? How does it compare with other earlier portraits by Gainsborough?” As the conservation process continues, McCurdy also looks forward to discovering other evidence that may become visible beneath the surface paint, and what it might indicate about Gainsborough’s painting practice. In fact, the undertaking, supported by a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project, already has uncovered new information of interest to art historians. During preliminary analysis, conservators found an L-shaped tear more than 11 inches in length, which data suggest was made early in the painting’s history. The damage may have occurred during the 19th century when the painting was in the collection of the Duke of Westminster and exhibited frequently. Further technical evidence combined with archival research may help pinpoint a more precise date for this tear, and even reveal its probable cause. “Project Blue Boy” Visitor Experience For the first three to four months during the year-long exhibition, The Blue Boy will be on public view in a special satellite conservation studio set up in the west end of the Thornton Portrait Gallery, where O’Connell will work on the painting to continue examination and analysis, as well as begin paint stabilization, surface cleaning, and removal of non-original varnish and overpaint. It then will go off view for another three to four months while she performs structural work on the canvas and applies varnish with equipment that can’t be moved to the gallery space. Once structural work is complete, The Blue Boy will return to the gallery where visitors can witness the inpainting process until the close of the exhibition. During the two periods when the painting is in the gallery, O’Connell will work in public view on regularly scheduled days and times. For the first in-gallery period, from Sept. 22 through January 2019 (estimated), visitors can watch the process each Thursday and Friday from 10 a.m. to noon and from 2 to 4 p.m., and on the first Sunday of each month from 2 to 4 p.m. A similar schedule will be in place during the second in-gallery session, estimated to begin in summer 2019. Schedule updates will be posted on the web at huntington.org/projectblueboy. When O’Connell is working in the gallery she might use any number of tools, the largest among them a Haag-Streit Hi-R NEO 900 surgical microscope that measures six feet in height. The state-of-the-art device has a long movable arm and optics that can magnify up to 25x to give the conservator a detailed view of the painting’s surface during the treatment stages, when special adhesives will be added to the areas of lifting paint. Many of the conservator’s hand tools will be showcased, giving visitors a chance to understand the precision inherent in the work. “When the painting is not in the gallery, visitors will still have plenty to see,” said O’Connell. A display with multiple educational modules will tease out details relating to the project and illuminate the painting’s structure and materials, condition and treatment plans, and an explanation of the conservation profession. An interactive light box will show the latest digital x-rays of the work; one iPad will allow visitors to explore more deeply the conservation science involved, and another will provide historical background on the painting and artist. Actual conservation tools will be on display, and behind a low wall, the temporary conservation studio will be in plain view, equipped with all the necessary trappings—work tables, easel, conservation lights, and exhaust units, as well as a whiteboard where O’Connell will post updates on what is currently happening and the times when she’ll be available to answer visitor questions. Also, specially trained docents will be stationed in the gallery throughout the run of the exhibition to illuminate the project and answer questions. After the close of the exhibition, the painting will go back to the lab for final treatment and reframing. Finally, in early 2020, The Blue Boy will be rehung in its former spot at the west end of the portrait gallery and unveiled as a properly stabilized masterpiece with more of the vivid pigments and technical brilliance it radiated when it debuted at the Royal Academy some 250 years ago again visible to viewers. The curators of “Project Blue Boy” plan to share their findings in lectures and publications after the completion of the project. The Huntington's website will track the project as it unfolds at huntington.org/projectblueboy. Related Programs “Project Blue Boy” will be accompanied by an array of public programs, including scholarly lectures, curator tours, and family activities. About The Blue Boy Thomas Gainsborough was among the most prominent artists of his day. Though he preferred to paint landscapes, he made his career producing stylish portraits of the British gentry and aristocracy. Jonathan Buttall (1752–1805), the first owner of The Blue Boy, was once thought to have been the model for the painting, but the identity of the subject remains unconfirmed. The subject’s costume is significant. Instead of dressing the figure in the elegant finery worn by most sitters at the time, Gainsborough chose knee breeches and a slashed doublet with a lace collar–-a clear nod to the work of Anthony van Dyck, the 17th-century Flemish painter who had profoundly influenced British art. The painting first appeared in public in the Royal Academy exhibition of 1770 as A Portrait of a Young Gentleman, where it received high acclaim, and by 1798 it was being called “The Blue Boy”–-a nickname that stuck. Henry E. Huntington (1850–1927) purchased The Blue Boy in 1921 for $728,000, the highest price ever paid for a painting at the time. By bringing a British treasure to the United States, Huntington imbued an already well-known image with even greater notoriety on both sides of the Atlantic. Before allowing the painting to be transferred to San Marino, art dealer Joseph Duveen orchestrated an international publicity campaign that rivaled those surrounding blockbuster movies today. In its journey from London to Los Angeles, The Blue Boy underwent a shift from portrait to icon, as the focus of a series of limited-engagement exhibitions engineered by Duveen. The image remains recognizable to this day, appearing in works of contemporary art and in vehicles of popular culture—from major motion pictures to velvet paintings. But beyond its cultural significance, the painting is considered a masterpiece of artistic virtuosity. Gainsborough’s command of color and mastery of brushwork are on full display in the painting, and they are expected to become more apparent as a result of “Project Blue Boy” conservation work. Mary Cassatt, Summertime, 1894, oil on canvas, 39 5/8 x 32 in. (100.6 x 81.3 cm), Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1988.25 Culturespaces and the Musée Jacquemart-André are presenting a major retrospective devoted to Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) in Paris through July 23 2018. Considered during her lifetime as the greatest American artist, Cassatt lived in France for more than sixty years. She was the only American painter to have exhibited her work with the Impressionists in Paris.

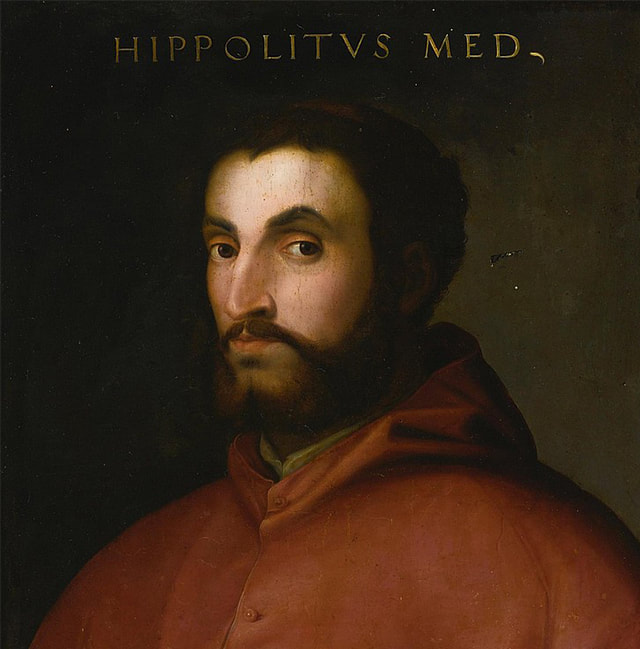

The exhibition focuses on the only American female artist in the Impressionist movement; she was spotted by Degas in the 1874 Salon, and subsequently exhibited her works alongside those of the group. This monographic exhibition will enable visitors to rediscover Mary Cassatt through fifty major works, comprising oils, pastels, drawings, and engravings, which, complemented by various documentary sources, will convey her modernist approach — that of an American woman in Paris. Born into a wealthy family of American bankers with French origins, Mary Cassatt spent a few years in France during her childhood, continuing her studies at the Pennsylvania Fine Arts Academy, and eventually settled in Paris. Therefore, she lived on both continents. This cultural duality is evident in the distinctive style of the artist, who succeeded in making her mark in the male world of French art and reconciling these two worlds. Just like Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt excelled in the art of portraiture, to which she adopted an experimental approach. Influenced by the Impressionist movement and its painters who liked to depict daily life, Mary Cassatt’s favourite theme was portraying the members of her family, whom she represented in their intimate environment. Her unique vision and modernist interpretation of a traditional theme such as the mother and child earned her international recognition. Through this subject, the general public will discover many familiar aspects of French Impressionism and Post-impressionism, along with new elements that underscore Mary Cassatt’s decidedly American identity. The exhibition brings together a selection of exceptional works loaned from major American museums, such as Washington’s National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Terra Foundation in Chicago; works are also loaned by prestigious institutions in France — the Musée d’Orsay, the Petit Palais, INHA, and the BnF (French National Library) — and in Europe, such as the Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon, and the Bührle Foundation in Zurich. There are also many works from private collections. Rarely exhibited, these masterpieces are brought together in the exhibition for the first time. "Portrait of Ms. Blair" by Sir Henry Raeburn, oil on canvas The “Old Masters,” an informal classification in art historical terms, generally refers to European artists dating from approximately the 1500s (the Renaissance) to the 1800s. They were fully trained artists who had become the Masters of their local artists’ guild. In reality, however, many paintings produced by followers of/ school of/ circle of, have also come to fit into today’s catch-all term. Many of the best-known painters of this geographically and historically broad area are considered Old Masters. In advance of a key season of Old Masters auctions, we take a look at this revered category through the lens of portraiture. Our editors spoke with two leading specialists: David Weiss, Senior Vice President and Department Head of European Art & Old Masters at Freeman’s Auctions and Iain Gale, Specialist in Fine Paintings, Sculpture and Scottish Art at Lyon & Turnbull, on why they are optimistic about the market for Old Masters portraits, and how buyers should begin their hunt. Starting a Collection: Old Masters Portraits“Portrait of Cardinal Ippolito de’ Medici” by Titian, 16th century, oil on panel Starting a collection of Old Masters portraits can be as broad or as narrow as your means, since this category features artists from a wide range of styles, movements, and geographic locations, including the Renaissance (Gothic, Early, High, Venetian, Sienese, Northern, Spanish), Mannerism, Baroque, the Dutch Golden Age, Flemish and Baroque, Rococo, Neoclacissism, and Romanticism. These schools include some of the most influential painters in Western art history: Titian, Jan Van Eyck, Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Durer, El Greco, Peter Paul Rubens, Artemisia Gentileschi, Diego Velazquez, Frans Hals, Jean-Antoine Watteau, Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, William Hogarth, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Francisco de Goya, William Blake, Eugene Delacroix, and more. Iain Gale advises that anybody wishing to start a collection of Old Masters portraits avoid what he calls a “scattergun” approach. Instead, Gale recommends choosing one centerpiece around which to build a collection, so that works chosen in the future are more likely to reflect the optimal taste of the first. For a new collector with a budget of around £20,000 (~$25,000) to invest, for example, Gale would suggest looking for a work by a Classical painter like Allan Ramsay (1713 – 1784), or the Romantic Henry Raeburn (1756 – 1823). David Weiss suggests that a good place to start is by looking to quality drawings by lesser known, but highly accomplished artists of the 17th and 18th centuries, as these “tend, on balance, to be more affordable than their equivalents rendered in oil.” He also suggests using a limited budget for an early engraving or etching. In offering different approaches to collecting, Gale and Weiss agree on one thing: the market for portraits, Old Masters or otherwise, is a complex one. Ultimately, they note, the motivation of the buyer underscores the value of a work. Collectors may buy portraits for any reason, from “self-aggrandizement to a serious interest in painting,” says Gale. For some, there is concern around buying a portrait of an unknown sitter, somebody else’s ancestry. Overlooked Old Masters While painting from the English Tudor and Stuart periods has always held a high price, much of it, says Gale, still appears stuffy and dark after “years of accumulated dirt and nicotine.” However, he adds, closely inspecting a corner of a work can help to show a painting’s true colors. David Weiss references top tier “school of” or “circle of” paintings, a suggestion he tempers with the caveat that, “this is not to say that landscapes, still lifes, and genre scenes which are direct copies of non-overlooked artist’s paintings deserve a great reception. It is to say that paintings of wonderful quality and skill, and those possessing aesthetic appeal, ought sometimes to sell for more money than they often do vis-à-vis their ‘name brand’ counterparts.” Weiss says that this can be a particularly wise investment because “school of” or “circle of” paintings “of a major artist can, with the passage of time, be determined to be by the artist after whom the work was first thought to be only modeled.” Self-Portraits in a Name-Driven Market “Portrait of a Gentleman Wearing an Embroidered Jacket” by Cornelis Troost, oil on canvas “The moment when a man comes to paint himself – he may do it only two or three times in a lifetime, perhaps never – has in the nature of things a special significance,” wrote Lawrence Gowing in his introduction to a 1962 exhibition of British self-portraits. According to Gale, there is no necessary correlation between value of a painting and whether it is a self-portrait because the value of a work can be determined by many factors. “There is a good market for self-portraits, particularly those that can comfortably be given to the hand of a first or second tier painter, a strong case can be made that there is a correlation between a portrait’s value and the identity of a sitter. It is difficult to argue against a portrait of major historical or noble figure outselling a portrait of a lesser known sitter,” says Weiss, before posing a hypothetical question: “An exceptional self-portrait by a lesser known hand or by a follower or student of a well-known artist versus a self-portrait of only passing quality by an important artist? My money is with the former in the current name-driven art market.” Unless a portrait serves a commemorative purpose, themes and narratives conveyed in a portrait may be subliminal. Such messaging and symbolism tends to include status, wealth, accomplishment, lineage, and power. However, Weiss says, these themes “are not always present in self-portraits, wherein many of the Old Masters sought to and succeeded in presenting themselves in a less grandiose light.” Quality is Key “Portrait of a woman washing clothes,” by Henry Robert Morland, oil on canvas Although the market today is undeniably driven by “name brand” artists, as David Weiss puts it, one crucial factor transcends all others, and both specialists return to the question throughout their responses.

“In my experience, one need only look at some of the offerings in the secondary Old Master auction catalogues of major houses as recently as the 1990s. In many of those sales, the ‘manner of’ and ‘follower of’ paintings that clearly appear to be secondary in quality would either not sell in 2017, or may not even be accepted for consignment in 2017 due to the ever increasing emphasis on quality and on works that are by, or at least have an affiliation with the hand of, an important artist or school,” says Weiss. Determining the value of a painting is a fine balance, the crucial element being an understanding of what motivates the buyer, says Gale. “It may be more visually appealing, and therefore of great value, if a work is by a good hand, even if it is by a minor artist.” Dr. Clare McAndrew (Art Basel)graph. Art Basel and UBS last week published the second edition of the Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report.Art Basel and UBS last week published the second edition of the Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report. Written by renowned cultural economist Dr Clare McAndrew, Founder of Arts Economics, The Art Market 2018 presents the results of a comprehensive and macro-level analysis of the global art market in 2017. Last year, the global art market grew by 12%, reaching an estimated $63.7 billion, with the United States retaining its position as the largest market and China narrowly overtaking the United Kingdom in second place. In 2017, dealer sales increased 4% year-on-year to an estimated $33.7 billion, representing a 53% share of the market, while public auction sales increased 27% to $28.5 billion. Much of the uplift in sales in the auction and dealer sectors was at the top end of the market; away from the premium price segment, overall market performance was mixed. A continuation of Dr Clare McAndrew's extensive research into this field, the report begins with an analysis of global sales data, including the key benchmark statistics on global transaction values, volumes and geographic market shares. It then continues in successive chapters by analysing the dealer and auction segments, art fairs and exhibitions (comprising a new stand-alone chapter), online sales, global wealth and art buyers, and economic impact metrics. Key findings of The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report include:

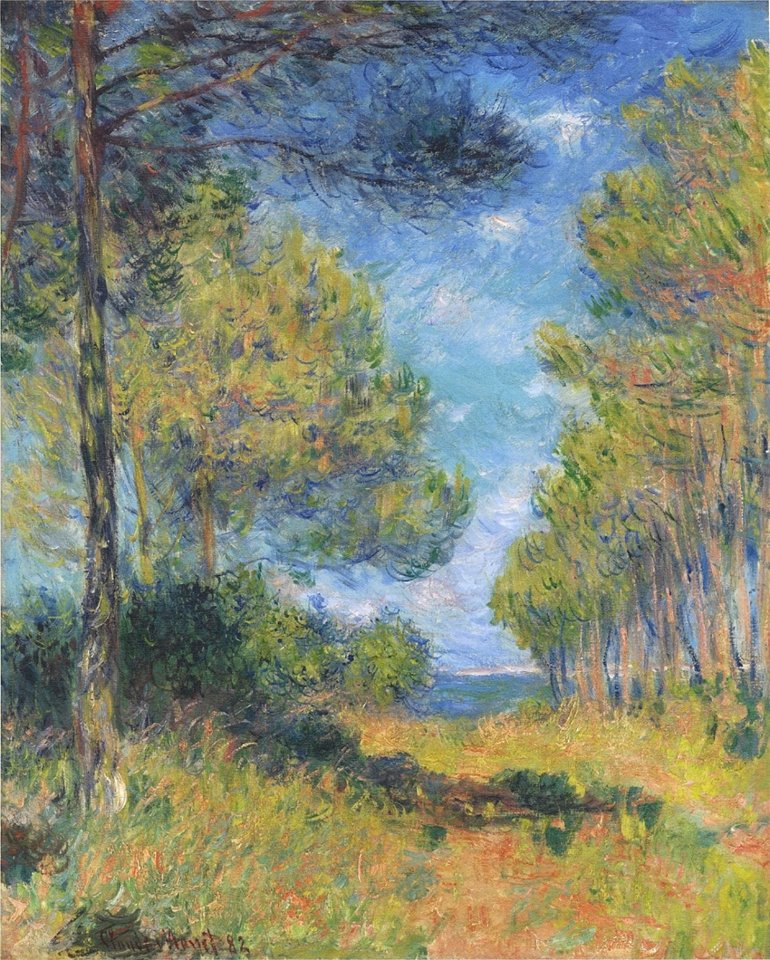

Clare McAndrew, Founder, Arts Economics said: "After two years of uncertainty and decline, the market turned a corner in 2017 with growth in the auction and dealer sectors, as well as at art fairs and online. Despite some remaining political volatility, robust growth in high-end global wealth, accelerating financial market returns, stronger consumer confidence and increased supply led to a much more favorable environment for sales. However, these industry-wide gains were driven by sales at the top end of the market, and away from this premium segment, performance was not all positive, with many businesses coming under pressure. This divergence in performance is a continuing concern, particularly as the majority of employment and ancillary spending comes from the very many other businesses in the art trade below the top tier. To maximize its economic impact, the market to be functioning well at all levels." Noah Horowitz, Director Americas, Art Basel said: "This report provides an unparalleled overview and analysis of the current state of the market. While the strong gains realized in 2017 as well as the field’s ever more global infrastructure are certainly reassuring, its top-heavy nature and rapidly changing dynamics, as captured in this report, have also never been clearer. Dr Clare McAndrew's findings are a must-read for any serious market participant or commentator, offering fresh insight on a wide range of the most pressing issues in today’s art business." Paul Donovan, Chief Economist, Global Wealth Management, UBS: said: "The performance of today's growing and globalized art market is a fascinating reflection of wider economic trends and highly correlated with GDP and HNW populations. Collecting is a passion that we share with many of our clients. Alongside our own exclusive art services, this collaboration with Dr Clare McAndrew and Art Basel is a natural fit for our ongoing commitment to the research and analysis of markets and economic data for our clients." "Path with Firs at Varengeville", 1882 |

AuthorsWriters, Journalists and Publishers from around the World. Archives

March 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed