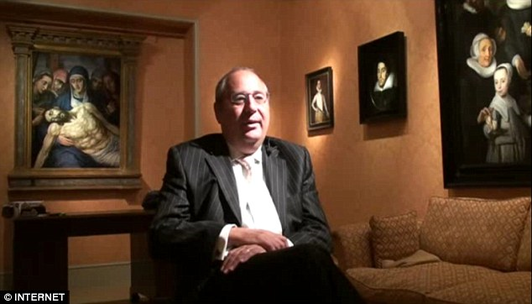

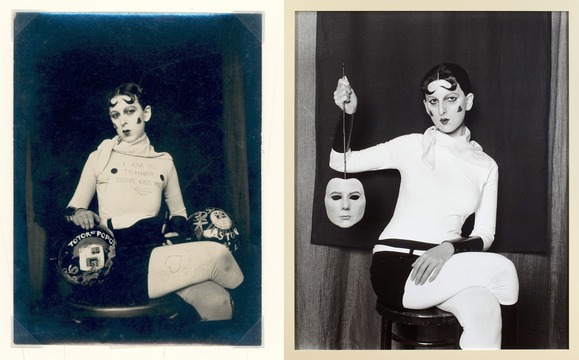

'Moriarty of the Old Master' pulls off the art crime of the century: Market in crisis as experts warn £200m of paintings could be fakesThe art world has been rocked by a haul of apparent forgeries by the ‘Moriarty of fakers’ that could cost investors £200 million. The suspect Old Masters – said to be by artists including Frans Hals and Lucas Cranach – have been described as the ‘biggest scandal in a century’. In one case, Sotheby’s has been forced to take back an £8.4 million ‘Frans Hals’ and The Mail on Sunday understands the auction house is now pursuing the London dealer who supplied the painting. Experts are particularly concerned because the alleged fakes are so difficult to spot from the real thing. Earlier this year, the Prince of Liechtenstein had a painting seized by French authorities amid suspicion that it was a forgery. And it is feared that up to 25 more ‘Old Masters’ will be revealed as possible fakes in the coming weeks after a judge launched an investigation. The paintings at risk could be worth up to £200 million. Yesterday, internationally renowned art dealer Bob Haboldt said: ‘This is the biggest art scandal in a century. There has been nothing like this since the “early Vermeer” scandal of the 1940s [when doubt was cast on a number of pictures by the Dutch master]. ‘It has put an entire generation of dealers on alert. The careful marketing of these highly sophisticated forgeries using primarily older materials has caught the market by surprise. The implications will be that buyers will insist on more guarantees, scientific and financial.’ The scandal is a matter of such embarrassment that few art figures are willing to speak openly, but one well-known dealer described the individual behind the copies as ‘the Moriarty of fakers’, because they are so brilliantly constructed. The scandal began to take shape earlier this year when a painting by German Renaissance master Lucas Cranach and owned by the Prince of Liechtenstein was seized by authorities at an exhibition in the South of France. Venus, dated 1531, had been sold by the Colnaghi Gallery in London in 2013 to the prince for £6 million but is now understood to be under examination by experts at the Louvre to assess its authenticity. The suspect Old Masters have been described as the ‘biggest scandal in a century’. Pictured, David by 'Gentileschi' (left) and Venus by 'Cranach' (right) The Cranach has been linked to a painting titled An Unknown Man, attributed to Dutch master Frans Hals, and a work called David With The Head Of Goliath, attributed to Italian master Orazio Gentileschi. Both paintings were bought by London dealer Mark Weiss, with the Hals being sold on to a distinguished US collector. Sotheby’s took a cut for brokering the ‘private treaty’ sale. However, when the collector, from Seattle, discovered the Hals painting was connected to the seized Cranach, he complained to Sotheby’s and their experts are understood to have subsequently decided it was a fake. Sotheby’s were later forced to reimburse the collector and are said to be threatening legal action against Weiss to recover their losses. Mr Haboldt said: ‘These three painters can be resold in the international market for millions and tens of millions. They are very hot names in the business and much sought-after. 'The works are difficult to detect as forgeries but they lack any credible provenance and references in the numerous publications about these artists. The latter should have made the principal dealers suspicious The willingness of Sotheby’s to accept the return of the portrait by Frans Hals and indemnify the buyer sets the stage for several more of these cases to come to light.‘But first, the international art world will have to wait for the results of the French investigation. Whispers in the trade have revealed a list of some 25 Old Masters produced by this particular forger’s workshop. I understand this list will be revealed soon.’ The Gentileschi is said to have been sold to a young US collector based in the UK, for an undisclosed amount, and was displayed at the National Gallery in London until recently. Haboldt said it is believed a ring of Italian forgers are behind the Old Masters and some of them have already been questioned by French authorities. The common thread to these paintings is they passed through the hands of unknown French dealer Giulano Ruffini, who claims he has discovered a string of Old Masters. Ruffini, 71, however, insists that he never presented any of the paintings as Old Masters. He said: ‘I am a collector, not an expert.’ Neither Mark Weiss nor Sotheby’s would comment, while Mr Ruffini’s lawyers could not be reached. The National Gallery said: ‘Gentileschi’s David With The Head Of Goliath has until recently been on temporary loan to the National Gallery from a private lender. ‘It was part of a small display of works by the artist that came to an end last week and it has now been returned to the owner. The gallery always undertakes due diligence research on a work coming on loan as well as a technical examination.’ By Adam Luck

0 Comments

Kenya’s Art Market Isn’t Exactly Booming |

AuthorsWriters, Journalists and Publishers from around the World. Archives

March 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed